I yelled at Allen last week. I could blame the lack of sleep, the arm that ached from the latest COVID-19 shot, or my very full class schedule. But the truth is that I was out of patience with my autistic adult son. I’d explained innumerable times over the past two weeks why his car was in the shop. That I understood he wanted his car back. That I knew it bothered his routine that his car was not sitting out front. I was calm. I was aware of the synapses in his brain that took longer to process information because the rich club network had failed to pare down the pathways when he was young. I knew his inability to multi-task resulted in a dogged determination to hang onto one thing at a time.

But I was tired.

“When will my car be done?” he asked the minute I walked in the door from a long day at school.

“I don’t know. They’re waiting for a part.” I dropped my schoolbag in the dining room and headed up the steps to change.

“Why don’t you know?”

“Because I don’t. Because I have nothing to do with the part. Please, please, stop asking.”

He didn’t. “I just want to know when I’ll get my car back. It’s MY car. I should know that. Can’t you find out?”

I paused halfway up the steps. “No. I can’t find out. I’m busy all day. The mechanic will call when it’s done!” I finished my climb and, totally over it all, leaned over the banister and shouted, “Sometimes it’s really hard to be your mother!”

I saw the shock on Allen’s face: eyes wide, mouth open. I seldom yelled. I went into my room and, for good measure, slammed the door.

I needed a minute. One minute away from parenting this wonderful but challenging adult. Maybe two. I sat in the rocker in the corner of my room, kicked off my shoes, and rocked.

Here was where I’d rocked all my babies to sleep. Even Allen, my youngest. I remembered the feel of him in my arms, all 8 pounds and 15 ounces in a blue sleeper, snuggled against my shoulder. I closed my eyes, remembering his baby smell, sweet and powdery, the warmth of him as he slumbered.

I regretted slamming the door. His brain worked the way it did. It was just the way he was born.

I rocked a little more, each motion the memory of a hope I’d had for him. He’d been a docile baby, easy to pacify. He would have friends who would hang around the house and go to school dances together. He was long and tall. Perhaps he’d play basketball. I dreamed of a career for him, a girl who would fall in love with his beautiful blue eyes. Grandchildren I could rock in this chair.

Not this. Not still living with me at past thirty, only able to work part-time at Walmart because social activities and sensory issues fatigue him. Not a brain that worked differently and confused both of us. Not a father who’d died too soon. Tears fell onto my lap.

One more minute, I told myself. I’d go downstairs and apologize. I’d be grateful to God for who Allen was, not what he was not. The rocking soothed me. It would be alright.

There was a soft tap at my bedroom door.

“Come in,” I said quietly, continuing my gentle rock.

Allen slipped in, his large frame filling the doorway. His beautiful blue eyes glistened with tears.

“It’s NOT hard to be my mother,” he said, his voice little more than a whisper.

I continued rocking, remembering the early diagnosis of learning disabilities, the years of special education classes, and the later news of autism. “Sometimes it is,” I said. “Sometimes I don’t think I’m very good at it.”

He stepped into the room and sat on the edge of my bed, reaching out a hand and laying it on my knee. “You ARE good at it.”

I kept rocking, the door slam still echoing in my mind. “Sometimes I don’t understand you.” I sighed.

He nodded and moved to the floor, where he rested his head on my lap. “I NEVER understand me,” he said. “At least you do sometimes. But you keep trying. That’s what a good mom does.”

We stayed where we were, rocking. He let me smooth his hair back from his forehead, accepting my touch. There’d been no rules to follow after the diagnosis of autism and my husband’s death. We did the best we could. We would just keep doing the best we could. There might be other slammed doors, other loud shouts, and other feelings of not being up to parenting this autistic adult.

But Allen and I are in this together. With his older siblings off to their own lives, and his father living in Heaven, we continue to function as a family of two.

With an occasional slamming door.

PARENTING AN AUTISTIC ADULT

Being the parent of an autistic adult can be a struggle. Allen and I have managed to find a life for the two of us since his father’s death, but there are still challenges. Lots of them. I can identify with these three from Psychology Today (2021).

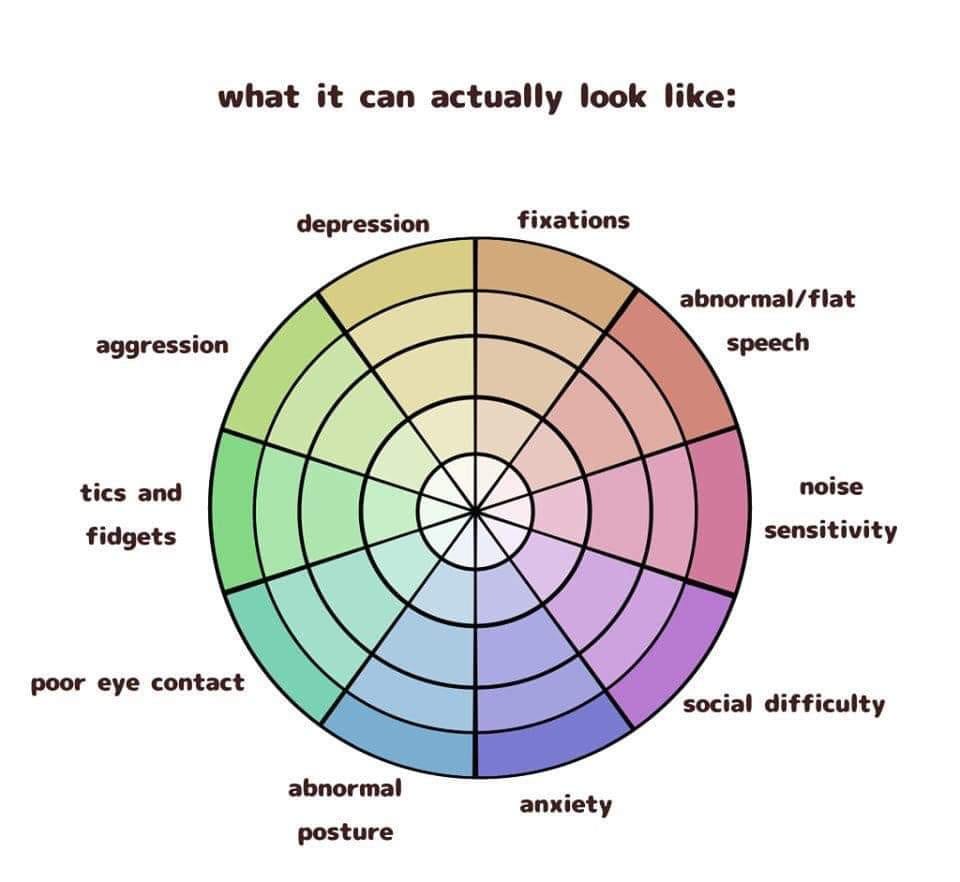

Losing sight of the challenges of ASD. I know that Allen does not function in the same way as his neurotypical siblings, but since he was not diagnosed until 24, I’ve needed to learn a lot about autism quickly. Up until a few months ago, Allen denied that he had autism. Autistic inertia—the inability to do, well, anything— is real. When he sits staring into space, he’s not ignoring chores or me. He’s simply recharging.

Communicating about necessary tasks and getting them done.

Allen is among the 20% of adults with autism who managed to achieve a college degree. Work, though, has been a challenge due to sensory issues and, regrettably, bullying by others who do not understand his quirks. If he works a day, he needs the next day to recharge. We work on a schedule each Sunday afternoon of work days and chore days. It’s not a perfect system, because while something as seemingly minor to me as running out of Mister Clean and having to use Pine-Sol instead is no big deal, it is to Allen. It can stop him in his tracks.

Challenges regulating anxiety, sadness, and anger.

Allen does not read social cues very well and can be outspoken. Anxiety often results in stimming such as arm flapping or feet stomping, but he’s learned to confine most of this to the house. His sadness–such as when his father died–can be all encompassing. Anger? Well, my walls used to suffer abuse but now it’s one particular folding table he pushes over. Poor table.

HOW TO HELP A SUBSTACK WRITER

To an author, an email list and reader engagement are vital. It shows potential publishers and agents that others are interested in our words. Unlike social media posts, we OWN our email lists. Every writer wants to see their lists grow.

Equally important is reader engagement. “Liking” a post you read on Substack is great, but there’s a bit more you can do to help your favorite writers find a publisher:

Comment on posts. My posts include a “comment” button. I see the comment as soon as you make it and I try to respond because I do appreciate the time you take.

Share with others. All of my posts also have a “share” button. You can share it on Substack or on your other social media outlets. You can even send it in an email and a message to someone.

Restack a post. This new feature on Substack allows you to “restack” a post so it comes to the top of the queue.

Consider becoming a paid subscriber. At the top of the post, you’ll see a button that says, “Upgrade to paid.” Most of my posts are free to read, but I really APPRECIATE those who pay a small fee to read what I write. I currently earn about $33 a month from subscriptions. I Timothy 5:17-19 says that a laborer is worthy of his hire and writing is HARD WORK!

PARENTING FAILURES

None of us are perfect, but we learn as we go. What are some of your parenting failures that have helped you grow?

Robin, thank you for reading and replying. I know there are many moms who also have a differently-abled child. I feel oh, so inadequate at times. Then I remember that God doesn't make mistakes. He gave Allen to me to be his Mom.

This is so, so familiar to me. Occasional slammed doors and apologies needed around here too. I don’t have the chance to have the same discussions with my son, but I’m hopeful he still understands somewhat when I explain, as you do, that it is hard but that doesn’t mean I will stop trying to be better for him. I really loved this scene with you and Allen and the rocking chair - it had me in tears.