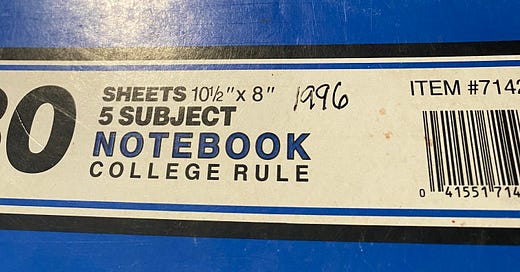

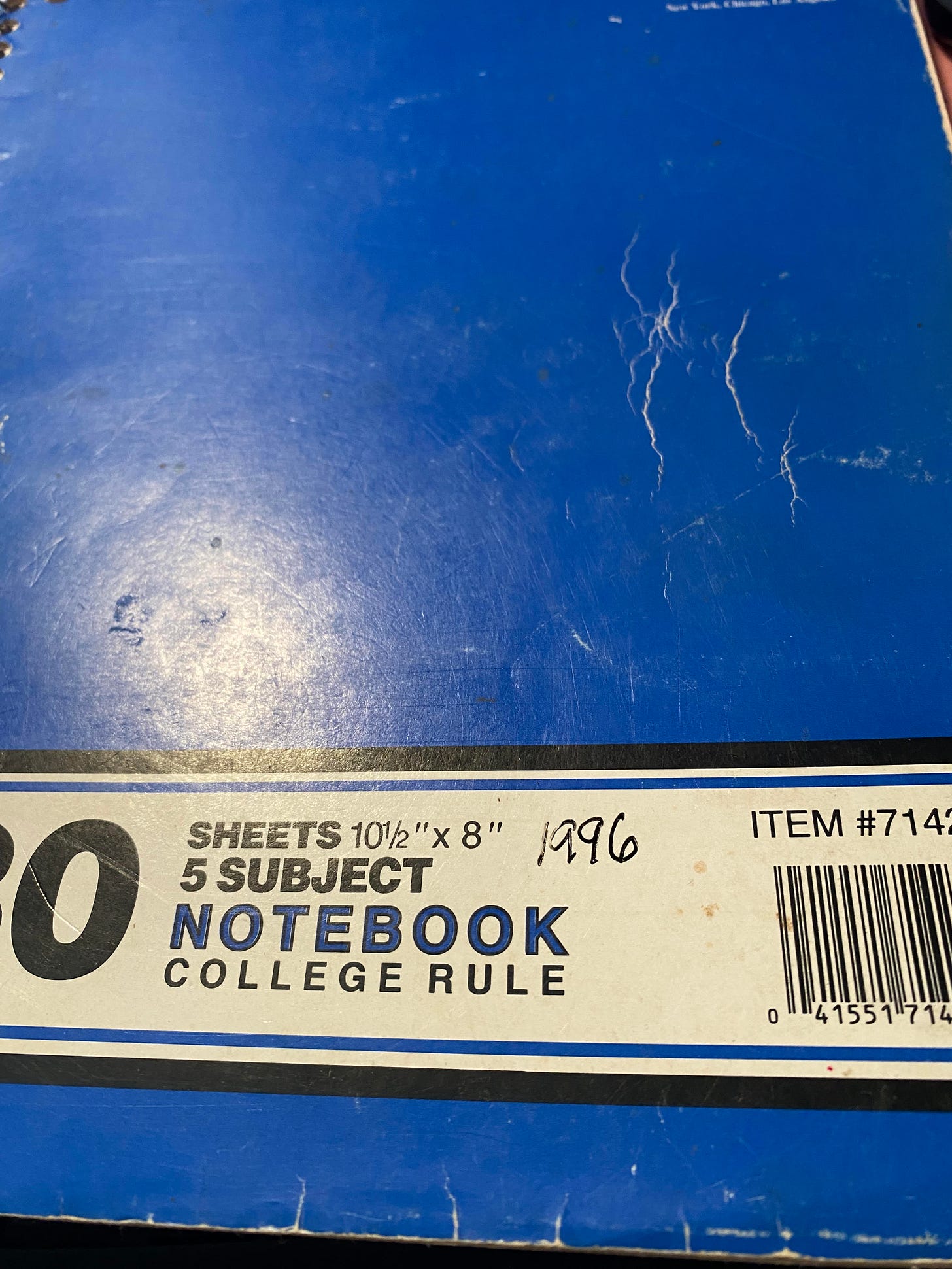

The blue one with the battered cover is the oldest of the more than 40 spiral notebooks piled around my home office. The date on the cover is 1996, the year I began my first full-time teaching position at a small private high school. The notebook started as a place to hold my morning Bible study, but it quickly morphed into a repository for notes about my classes and seed ideas for stories.

And then it saved my life. Or, to be more precise, it saved my sanity. 1996 was also the year my previously placid husband began to slam furniture into walls, dribble a basketball on the outside court late into the night, or wake me up out of a sound sleep to tell me he was scared, although he couldn’t say why. It was the year my kids and I often escaped to the peaceful waters of the river park when Ron started ranting that no one loved him or cared about him. 1996 was the first time my beloved husband was committed to a psychiatric facility.

It wasn’t the last.

I took Ron to therapists and psychiatrists and psychologists in quick succession, paying out- of- pocket costs and waiting in chilly waiting rooms, scribbling furiously into the blue notebook and its successors. I wrote about the frightening changes in Ron, worried about what they would mean to our marriage, and feeling the increased financial burdens falling onto my shoulders. I wrote about my fears that Ron would not be able to work and how to protect my children from what my son started to call, “The live grenade that is Dad.”

While Ron worked with doctors behind closed doors to try and solve the problems that were roiling like ocean waves through his mind, I etched my worries in permanent ink on paper lined with tranquil blue.

In 1981, Dr. James Pennybaker of the University of Texas began his study on expressive writing and its effect on physical health. His directions to the study participants were simple: “Write your deepest thoughts and feelings about the most traumatic experiences of your entire life.” Mine were so deep the paper was scarred, the pen indentations three-dimensional. My furious outpourings did not solve Ron’s issues.

But they helped me find the strength to handle mine.

Dr. Pennybaker’s study revealed several positive impacts the simple act of writing could have:

Decreased anxiety, blood pressure, muscle tension, pain, and stress

Enhanced lung function and immune systems

Improved memory, sleep quality, and social life

Increased grades and work performance.

He summed it up this way: “By writing, you put some structure and organization to those anxious feelings.”

The years of mental issues–eventually identified as bipolar disorder–led to the car accident and its traumatic aftermath, and the piles of spiral notebooks grew and held the thoughts I could not say to others.

Until now.

Writing has been a catharsis in my life, but the experiences I have had might also aid others. Readers have responded to the shared trials of widowhood and parenting an adult on the autism spectrum. Sharing our experiences can make us feel less alone. Recently, I watched an interview from Flourish Writers with Kathy Lipp from Writing at the Red House. Kathy suggested that writers “write about 7 degrees of North” to tell the hard things.

I’ve got more than 40 notebooks. And I’m ready to write.

Are there hard things in your life you are willing to share that might help others with their journeys?

Unfortunately I left several notebooks of ranting behind after the divorce. My impressions were at times so deep the paper gave way…torn in two. No diagnosis about my ex but I’m leaning to bipolar as well. Fits of anger and yelling when seconds ago it was quiet. I then received, “you know what you did!” That was when I asked what was wrong. You and I have more in common than perhaps we knew. At least we wrote…saving what sanity we had left.

Writing can be a saviour, it can also help others, as yours does. Thanks for sharing your journey. Each post shows your strength and determination to live a dignified life, no matter the circumstances. An inspiration.