The Laundry Diaries Part 2.

What I learned about neurodiversity from two years at the laundromat

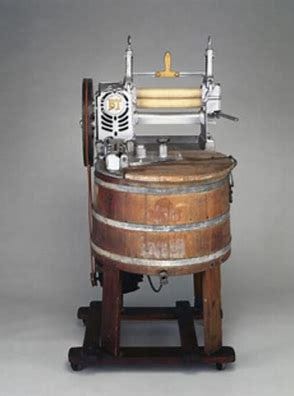

I’m ready to give up. Despite our best efforts, our washing machine remains unable to perform its created function. We went so far as to take the back panel off the damned thing, even though neither Allen nor I knew what we were looking for.

But the laundry is piling up and my selection of “school clothes” is limited. So on Saturday, I make an announcement over breakfast:

“We need to do something about the laundry.”

Allen shrugs. “I did what I could,” he says. “I got the water out of the machine. I don’t know what else we can do.” My son is content to wear the same clothes day after day so he sees no problems with a non-functioning washer.

“You did your best,” I tell him. “But we need to do the laundry. I need clothes for the week. So, I think we have two choices.” I hold up one finger. “We can call a repairman.” I hold up another finger. “We can go to the laundromat.”

I see the wheels in Allen’s head begin to turn and I wait patiently. People unfamiliar with autism in adults might tell me to just make my own decision and be done with it, but giving Allen choices accomplishes two things: it shows that I respect him as an adult, and it gives him a chance to see things from another perspective.

Giving choices to those with autism can improve many scenarios. Yes, autism makes it harder to communicate for all parties involved, but it’s by no means impossible.

Madison House Autism Foundation.

I go about clearing up the breakfast dishes while Allen hashes over the choices. I know that he is adverse to strangers in the house; the house is his safe space where things are quiet and regulated to his liking. But a laundromat is a busy place with loud noises, strong scents, and new people. I try to maintain an aloof stance as he processes it. As much as possible, we try to avoid sensory overload which can lead to emotional meltdowns.

Change, whether in one’s self or the environment, typically causes sensory overload, since change affects the person’s ability to process the sensations accompanying that change.

Dr Kenneth Roberson

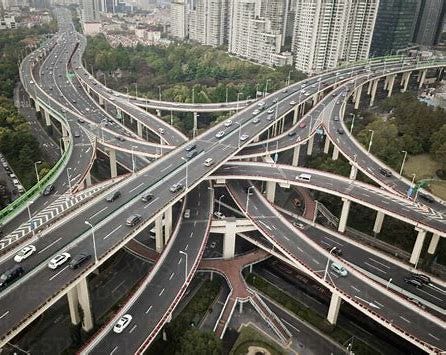

It takes Allen a full ten minutes to respond. I know he’s heard me, so I don’t repeat the choices. I pour myself a cup of tea and settle into my favorite chair. The Rich Club Network that carries information across a vast highway of connections in Allen’s brain cannot be rushed. It’s like finding the best route from Shangai to New York. He needs time to process.

Eventually, he appears in the living room, shoulders sagging, resigned to acceptance of something he cannot control. He takes a deep breath.

“I guess we can go to the laundromat,” he says. “I mean, just this ONE TIME.”

I nod. “Thank you,” I say. “I need you to help me carry the baskets, so I’m glad you can come.”

“I guess,” he says and heads upstairs to gather the laundry. I get the detergent and car keys.

“You know,” he says as we load the laundry into my car,” I’ll bet we don’t need a repairman. I’ll bet that I can invent a washer we can use from now on.”

Now I’m going to need some time to process.

LESSON LEARNED: When possible, give choices. Choices give back power that was taken away.

Was there a time you needed to give someone a choice between what my grandmothr would have called “the rock and the hard place”?